Weather fact check: Deaths

Exposure to cold or hot temperatures is associated with premature deaths. Recently I read that “Extreme heat in the United States is the number one weather-related cause of death”. Is this true?

Exposure to cold or hot temperatures is associated with premature deaths. Recently I read that “Extreme heat in the United States is the number one weather-related cause of death”. Is this true?

It is supported by the US National Weather Service, but not by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDCP). The Weather Service says that the 30-year average (1992-2021) fatalities for excess heat was 164 and for excess cold was 35. That heat-related deaths were 4.7 times as prevalent as cold-related ones. But this data is often based on media reports.

Based on information on deaths that were attributed to weather-related causes from death certificates in the United States during 2006–2010, the CDCP found that nearly one-third of the deaths were attributed to excessive natural heat, and almost two-thirds were attributed to excessive natural cold. So you might get different answers depending on how you determine or select the mortality data! See the Appendix for more information on the relationship between mortality and ambient temperature.

The determination of deaths due directly to weather-related events has a high degree of uncertainty. So in this post we look at all deaths (including those that are due both directly and indirectly to weather-related events and those unrelated to the weather). This avoids the problem of data selection and cherry-picking.

Mortality in France

Monthly mortality data for France (1994 to 2022) is graphed below. The mean mortality is indicated by a 13-month moving average.

The mortality rate shows a seasonal pattern with a winter peak (around January) and a summer trough (around June to September). This is similar to the mortality in 16 European countries (1998-2002) which showed low summer mortality from June to September and a winter peak in January and February.

The mortality rate shows a seasonal pattern with a winter peak (around January) and a summer trough (around June to September). This is similar to the mortality in 16 European countries (1998-2002) which showed low summer mortality from June to September and a winter peak in January and February.

The short-term trend in the mean mortality is:

– level (1994-1999)

– decreasing (2000-2005)

– increasing (2006-2022), with a higher level in 2020-2022 presumably due to COVID-19.

The record examined is too short to indicate any long-term trend in mortality.

During 1995-2019, mortality was typically above the annual mean for 5 months (ranging 4-6 months) in the winter and below the annual mean for 7 months (ranging 6-8 months) for the remainder of the year (including summer).

The typical peak monthly winter mortality (1995-2019) was 15% (ranging 10-30%) above the annual mean mortality.

During this period, the following heatwaves occurred in France: August 2003; July – August 2006; July 2010; June – July 2012; July – August 2013; July -August 2015; July 2019; and June – August 2022.

The brief peak mortality in August 2003 is an exception to the usual pattern. This coincides with a major heatwave. The mortality rate across Europe shows three main peaks during this summer: a peak on June 13, a double peak on July 16‐2 and a major peak on August 12-13. In August 2003 the peak monthly mortality rate was similar to the peak winter rates, but the summer mortality rate (indicated by the width of the peak) was appreciably lower than the usual winter rate. There was no other elevated mortality associated with heatwaves during 1994-2022.

Now France has a National Heat Wave Plan and in 2019 it was evident that this had cut mortality by 90% in a heatwave that was comparable to that in 2003. This early warning system safeguards communities when extreme heat is predicted. So the nation is better prepared to survive a heatwave.

Mortality in Australia

Mortality has a definite cyclical pattern in Australia (de Looper, 2002; Gregory, 2022). It is greatest in winter and least in summer. de Looper (2002) found that deaths typically peak in August and trough in February.

Monthly mortality data for Australia (2015 to 2022) is graphed below. The mean mortality is indicated by a 13-month moving average.

The mortality rate shows a seasonal pattern with a winter peak (around July-August) and a summer trough (around December to March).

The mortality rate shows a seasonal pattern with a winter peak (around July-August) and a summer trough (around December to March).

The short-term trend in the mean mortality is:

– increased slowly (2015-2020)

– increasing more rapidly (2021-2022), presumably due to COVID-19. There were 190,775 deaths in 2022, which is significantly higher than usual and it is not considered to be a typical year for mortality in Australia. The seasonal pattern of mortality seems to be returning to normal levels in 2023.

The record examined is too short to indicate any long-term trend in mortality.

During 2015-2019, mortality was typically above the annual mean for 5.5 months in the winter and below the annual mean for 6.5 months for the remainder of the year (including summer).

The typical peak monthly winter mortality (2015-2019) was 15% (ranging 12-50%) above the annual mean mortality.

The brief peak mortality in January 2022 is an exception to this pattern. Due to the La Nina, temperatures in this month were generally below normal and rainfall was above normal. So it wasn’t associated with a heatwave. Therefore, COVID-19 is the most likely cause of this mortality anomaly.

The decreased mortality in the winter of 2020 was due to the COVID-19 control measures adopted across Australia which reduced deaths from respiratory diseases, including influenza and pneumonia. But seasonal mortality increased from mid-2021 despite 50% of the population being vaccinated by September 2021.

During this period, the following heatwaves occurred in Australia:

– January-February 2016

– January 2017

– January 2019

– December 2019-January 2020, when there were widespread bushfires

– January 2021

There are no significant heatwave impacts in the mortality data. There are some peaks in the mortality curve near some of these dates, but their magnitude is small.

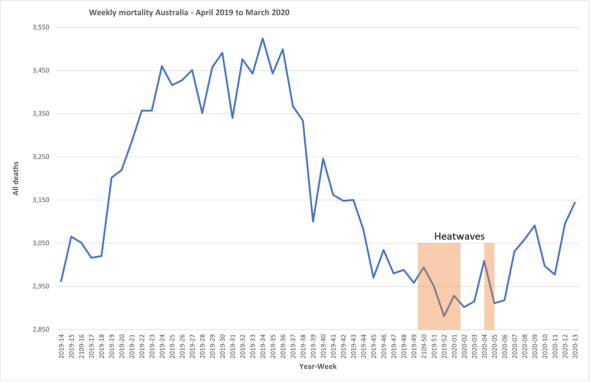

Weekly mortality data were examined for December 2019-January 2020 when there were record-breaking heatwaves across Australia. The heatwaves occurred during:

– The last three weeks of December 2019 (weeks 50-52)

– The first week in January 2020 (week 1)

– The last five days of January 2020 (part of weeks 4-5)

There were no major increases in mortality during these time periods (see graph below).

Mortality in the United States

Mortality in the United States

As in France and Australia, U.S. deaths have regular annual cycles — normally increasing in the winter and declining in the summer months. Between 2010 and 2019 the highest number of deaths were in December, January or February. And the lowest number of deaths occurred in July and August. The death rates in winter months have been 8-12% higher than in non-winter months.

In the US, COVID-19 also disrupted the seasonal pattern in mortality, and increased the mean mortality levels.

Discussion

Mortality has a definite seasonal pattern in France, Australia and The Unites States. And the seasonal weather pattern has more impact on mortality than shorter-term weather events. It is generally believed that seasonality in mortality increases with latitude as is the case for influenza. And there are no significant seasonal differences in mortality in equatorial regions.

In France the typical peak monthly winter mortality (1995-2019) was 15% (ranging 10-30%) above the annual mean mortality. There was only one summer with excess mortality due to a heatwave. However, this has not been repeated because of France’s National Heat Wave Plan.

In Australia the typical peak monthly winter mortality (2015-2019) was 15% (ranging 12-50%) above the annual mean mortality. There were no significant increases in mortality during heatwaves in Australia between 2015 and 2019. This includes December 2019 to January 2020, when there were widespread bushfires. Hanigan et al., (2021) found that in 1968-2018 the summer mortality increased more rapidly with time than the winter mortality and predicted that in future summer deaths will be more than winter deaths. But according to their data and assumptions that would take about 85years.

Conclusion

In the mid latitudes more people die (directly or indirectly) of cold than of heat. This means that more people die in the winter months than in the summer months. And the impact of the seasonal weather pattern on mortality dominates the impact of short-term extreme weather events. Therefore, extreme heat is not the number one weather-related cause of death in these countries.

When someone mentions the danger of death in heatwaves, remember that more people die in winter (when there are no heatwaves) than in summer.

With the focus on alleged global warming, there is a danger of health authorities failing to address the effect of cold temperatures when developing health promotion strategies. I say “alleged” because the atmosphere is more complicated that the mathematical models used to represent it – just like the complexity of the epigenetic code of the 4-dimensionsal genome exceeds that thought a few decades ago.

Appendix: Mortality and ambient temperature

The natural hazards that led to the largest loss of life across the earth are droughts, storms and floods. These have greatest impact in third world countries.

Between 2009 and 2019, there were 682 deaths in Australia due directly to weather-related events (41% excessive cold; 37% excessive heat; 15% storms and floods) (Peden, Heslop and Franklin, 2023).

Zhao Q et al. (2021) investigated the relationship between ambient temperatures and mortality across the world between 2000 and 2019. They found that 9.4% of deaths were associated with non-optimal temperatures. 8.5% of these were cold-related and 0.91% were heat related. So most excess deaths were linked to cold temperatures. Cold-related deaths were 9 times as prevalent as heat-related ones! Eastern Europe had the highest heat-related excess death rate (they are less prepared for hot temperatures), and sub-Saharan Africa had the highest cold-related excess death rate (they are less prepared for cold temperatures). They stated that most deaths attributable to hot and cold temperatures were brought forward by at least 1 year.

An epidemiological study of deaths (1985-2012) in 13 countries (Gasparrini et al, 2015), found that cold-related deaths in the U.S. were about a factor of fifteen higher than heat-related deaths. Cold deaths outnumbered heat deaths by a factor of twenty when averaged over all 13 countries studied.

However, sometimes these studies are criticized because they did not control for the seasonal cycle in death rates; deaths are always higher in winter, due to influenza and other non-weather-related factors. Or for confusing seasonal mortality with temperature-related mortality. But this is nonsense! Influenza is a weather-related factor – it is more prevalent in winter when temperatures are colder. If influenza is a weather-related disease, it should be included and not excluded. And the seasons are weather related, so they should be included.

Kinney PL et al. (2015) has warned that cold temperature is not directly responsible for most winter excess mortality. This means that it probably has an indirect impact on mortality.

References

de Looper, 2002, “Seasonality of death”, Aust. Inst. Health & Welfare, Bulletin No. 3, October 2002.

Gasparrini A et al., 2015, “Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observational study”, The Lancet, 386 (9991), 369-375.

Gregory G et al, 2022, “Learning from the pandemic: mortality trends and seasonality of deaths in Australia in 2020”, Int. J Epidem. 51 (3), 718-726.

Hanigan IC, KBG Dear and A Woodward, 2021, “Increased ratio of summer to winter deaths due to climate warming in Australia”, 1968–2018, Aust New Zealand J Public Health, 45 (5), 415-530.

Kinney PL et al., 2015, “Winter season mortality: will climate warming bring benefits?”, Environ. Res. Let., 10 (6), June 2015.

Peden AE, D Heslop, RC Franklin, 2023, “Weather-Related Fatalities in Australia between 2006 and 2019: Applying an Equity Lens”, Sustainability 2023, 15(1), 813.

Zhao Q et al., 2021, “Global, regional, and national burden of mortality associated with non-optimal ambient temperatures from 2000 to 2019: a three-stage modelling study”, Lancet Planet Health, 5, e415–25, July 2021.

Written, July 2023

Leave a comment