Is the Torah fact or fiction?

Were the ancient Israelites ever really slaves in Egypt? Did the Exodus really happen? Was the Torah (see Appendix) written by Moses in the mid second millennium BC, or by Jews about 1,000 years later? Is it fact or fiction?

Were the ancient Israelites ever really slaves in Egypt? Did the Exodus really happen? Was the Torah (see Appendix) written by Moses in the mid second millennium BC, or by Jews about 1,000 years later? Is it fact or fiction?

In this post, the content of the Torah is examined to see how it matches with the existing archaeological record to help throw light on its origin. When was the Torah written?

What the Old Testament says

The Bible says that Moses wrote the Torah, ‘Moses then wrote down everything the Lord has said” (Ex. 24:4ESV). And “Moses had finished writing the words of this law [Torah] in a book to the very end” (Dt. 31:24). Joshua called the book of Exodus, “the Book of the Law of Moses” (Josh. 8:31).

The archaeological record and the Scriptures show Moses could write. Because Moses was raised in the royal court as a nobleman, he was taught to read and write, “Moses was instructed in all the wisdom of the Egyptians, and he was mighty in his words and deeds” (Acts 7:22). As an educated nobleman, Moses would have learned Egyptian; and as an Israelite, he also would have known whatever form of Hebrew existed at the time. The Torah we have was written in Hebrew; and though some of the Hebrew terms demonstrate the author’s familiarity with Egyptian, nothing indicates the text was translated from Egyptian. Literacy was widespread among the Israelites in the time from Moses because they were instructed to write the commandments on their doorposts (Dt. 6:6-9).

What the New Testament says

Jesus identified Moses as the author of the Torah (Mt. 19:1-9; Lk. 16:29, 31; 24:27, 44; Jn. 5:46-47). He also referred to the Torah as “the book of Moses” (Mk. 12:26).

And Paul identified Moses as the author of the Torah (Acts 26:22).

As these people lived about 2,000 years closer to that time, their view of this history should be more reliable that that of anyone today.

What modern scholars think

The consensus of modern scholars is that the Torah does not give an accurate account of the origins of the Israelites because it was written about 1,000 years later than that time. They say that no clear extrabiblical evidence exists for any aspect of the Egyptian sojourn, exodus or wilderness wanderings. But absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

They don’t believe the biblical text is accurate. For example, they think that the 480 years in 1 Ki 6:1 is problematic because 480 is 12 times 40 and both of these numbers have symbolic meaning in the Bible! They assume that the rhetorical function outweighs the historical intent. This enables them to disregard the Biblical chronology which says that the exodus was about 1450 BC (966 BC plus 480 years).

For Bible critics, facts and evidence are much less important than the grand agenda: to destroy the belief that the Torah is the inspired Word of God by recasting it as an epic tale of fiction.

What the Bible says

Most of this post comes from an article by archaeologist Christopher Eames of the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology. He asks, can we find evidence within the Torah that indicates the time period when it was written?

What does the language of the Torah tell us? What if the words and phrases used within the “books of Moses” reflect an accurate, perhaps even eyewitness, account of Egypt as it was in the mid-to-late second millennium—generally known as the New Kingdom period, circa 1550–1075 BC? Are there etymological clues proving the author (Moses) experienced the events and culture he recorded?

Or does evidence suggest the author or authors were far removed from New Kingdom period Egypt, with only a hazy understanding of early Egypt’s language and culture?

Phraseology

Moses told the Israelites, “You shall remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the Lord your God brought you out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm” (Dt. 5:15ESV).

These terms, a mighty hand and an outstretched arm, are used numerous times throughout the Hebrew Bible—but always in the context of the Exodus. “The Bible could have employed that phrase to describe a whole host of divine acts on Israel’s behalf, and yet the phrase is used only with reference to the Exodus. This is no accident”.

There is a fascinating historical reason this phrase is only associated with the Exodus. It’s actually a unique pharaonic “victory” expression—one common during Egypt’s New Kingdom period.

“It is not until the Middle Kingdom (1970–1800 BC) that we begin to see expressions related to the conquering arm of pharaoh appearing …. [This] continues with even greater frequency in the New Kingdom”.

In Egyptian records, pharaohs Thutmose II and IV are named the “Mighty of Arm.” Senusret I is lauded in the “Hymn of Sinuhe” for “strong arm … a champion [with] arm outstretched.” Relief representations of pharaohs smiting their enemies with their right hand are also common. “In no other ancient Near Eastern culture do we encounter such portrayals of the right hand”. It is specific to Egypt—and especially Egypt in the New Kingdom period. And what do we see in the Torah? This pharaonic phrase turned on its head: It is God, by His “outstretched arm,” that destroys the pharaoh.

Another phrase found often in the Bible is praise for God destroying Israel’s enemies like chaff (or “stubble,” Ex. 15:7). This saying also appears in New Kingdom period Egypt (specifically, within Ramesses II’s Kadesh poem). It is not known in any other Near Eastern text.

The Kadesh poem written by Pharaoh Ramesses II following his victory against the Hittites, is remarkably similar to with the “Song of Victory” recorded in Exodus 15 (after the Israelites crossed the Red Sea). A comparison of the two texts shows that the author of this biblical “song” (Moses) must have been familiar with the courtly, royal language used in Egypt’s New Kingdom period.

There is a direct correlation between the entire book of Deuteronomy—Moses’s “final address” to the people of Israel—and the second-millennium BC “suzerainty treaties,” of a layout specific to the second half of the second millennium BC. Also, the layout of Deuteronomy is similar to the layout of the treaty between Mursili and Duppi-Tesub (a 13th-century BC Hittite treaty). Both have a near-identical layout: a preamble, historical background, treaty stipulations, invocation of witnesses, deposition of written copy of treaty, and a conclusion of curses and blessings for obedience and disobedience to the treaty.

Other evidence also shows that the author of the Torah was familiar with the layout of courtly, formal second-millennium treaties.

Geography

Another notable point is that the author of the Torah was familiar with the geography of New Kingdom period Egypt. Moreover, while the author’s descriptions of Egypt’s landmarks are detailed and accurate, he appears to be less familiar with the geography of the land of Canaan. If the text were composed much later by authors in the land of Judah, we would expect precisely the opposite. Instead, the text fits well with a princely Egyptian-origin author who was denied entry into the Promised Land at the end of his life (Num. 20:12).

“The author of the Torah is familiar with the land of Egypt. He is familiar with the reeds in the Nile (Ex. 2:3) and knows that it would be safe to put a child in a basket in that river. … The author feels a need to explain things in Canaan with reference to things in Egypt.” Deuteronomy 11:10-12, for example, highlights the method of gardening in Egypt, and how these methods will no longer be necessary in the land of Canaan because of more rainfall.

Note the following seemingly arbitrary statements, all of which use Egypt as a reference for otherwise obvious features in the Promised Land. Genesis 13:10 describes a “plain of the Jordan” as being “like the land of Egypt”. In Numbers 13:22, the author writes, “They went up into the Negeb, and came to Hebron …. Hebron was built seven years before Zoan in Egypt.”

Genesis 33:18 reads, “Jacob came safely to the city of Shechem, which is in the land of Canaan” It doesn’t make sense for a Jewish author writing in the middle of the first millennium to identify the location of a such a major, well-known city. Yet it makes perfect sense that an author writing from outside Canaan, whose immediate audience was equally unfamiliar with Canaan, might use such language.

What about the central city Jerusalem? It is named as such nearly 700 times throughout the Hebrew Bible—yet not once in the Torah (despite the fact that this region is mentioned—Genesis 22). Its first mention in this form is in the book of Joshua, during the conquest (Josh. 10:1). Surely late-date writers would not have forgotten to mention such an important Judean city by this name.

Flora and fauna

The author of the Torah was also familiar with the diet fed to slaves in Egypt. Numbers 11:5 states that the Israelite slaves were fed leeks and onions. Herodotus, the fifth-century BC Greek historian, wrote in his Histories that during a tour of the pyramids, he observed an inscription that stated the workmen were fed leeks and onions (2.124).

The author of the Torah was also familiar with Egyptian botany. Acacia wood is mentioned nearly 30 times in the Torah (primarily in the context of building the tabernacle), and only four times in the rest of the Old Testament. This makes sense, as it is a wood native to Egypt and the Sinai Peninsula. (In the four times acacia wood is mentioned outside the Torah, it is never used to describe the trees existing in Israel.)

Unsurprisingly, the Hebrew word used for this wood is of Egyptian derivation. Not only that, it resembles a very early Egyptian spelling (which actually changed during the New Kingdom period). “The facts that shittim is a word of Egyptian origin and that this tree provides the only suitable wood for construction use [while in the wilderness], lends authenticity of this element of the wilderness tradition”.

The author of the Torah also appears to have been familiar with Egyptian diseases. Deuteronomy 28:27 reads: “The Lord will strike you with the boils of Egypt, and with tumors and scabs and itch, of which you cannot be healed”. According to 17th-century theologian, linguist and Egyptian expert Johann Vansleb, the “boils of Egypt” was a recurrent disease specific to the seasonal rising of the Nile. First-century AD historian Pliny the Elder wrote of an “Elephantiasis” (to which this disease has been linked) that was “originally peculiar to Egypt” and specifically the area of Upper Egypt, home of the native Egyptian dynasty (Natural History, 26.5). First-century BC philosopher Lucretius attributed this disease to the Nile River.

Names

Finally, consider the etymology of the names of some of the primary figures in the Torah. Many are distinctly Egyptian in origin.

The protagonist of the Torah is Moses. This name has long been associated with the common Egyptian name Mosis or Mose. Egyptian records show this was an important name in royal Egyptian society, and one that appears primarily during the New Kingdom period. In Egyptian, the name Moses means “born of” (a meaning inferred in Exodus 2:10, which describes Moses’s naming). Other New Kingdom figures with the same name include Tuthmose or Tuthmosis (“born of Tuth”), Ahmose, Amenmose, Ramose, Kamose, Wadjmose, Ramesses, etc. It only makes sense that an Egyptian princess, who was part of a royal dynasty frequently using this name element, would use it for her adopted son.

Then there’s Aaron, Moses’s assistant. The meaning of this name in Hebrew, pronounced Aharon, is famously unclear. However, it is a good parallel to the ancient Egyptian name Aharo/Aha-rw (with the added suffix “n”), an Egyptian name that means “lion warrior.”

Moses and Aaron’s sister was named Miriam, a name long identified as Egyptian in origin. The initial element, Meri, is a common Egyptian one meaning beloved, which is followed by an attached theophoric (deity) element—in this case most often presented as Meri-Amun, “Beloved of [the god] Amun.”

Things really get interesting with the name pharaoh. One of the most frustrating observations about the Exodus story, at least for historians, is the author’s failure to identify Egypt’s pharaohs by name. In fact, the Bible does not begin to identify Egypt’s pharaohs by name until the 10th century BC.

Is this the sign of an ignorant late author? Hardly—especially when considering the incredibly accurate details described above and the fact that access to such historical names would have been simple to acquire.

Yet this phenomenon fits perfectly with New Kingdom period Egypt. As frustrating as it is for 21st-century scholars, this lack of reference to the pharaohs fits with literature of the mid-to-late second millennium BC. Ancient Egyptian records show that while they did have specific names, the primary title used when referring to Egypt’s leaders during this specific period was simply pharaoh.

In his book Israel in Egypt, Professor Hoffmeier explains in detail how the term pharaoh began to be used in the 15th century (beginning with the reign of Thutmose III) and then fell out of use in the 10th century. “By the Ramesside period (1300–1100 BC), ‘Pharaoh’ is widely used. … From its inception until the 10th century, the term ‘Pharaoh’ stood alone, without juxtaposed personal name. In subsequent periods, the name of the monarch was generally added on. This precise practice is found in the Old Testament … suggestive of the period[s] of composition.”

The use of the singular term pharaoh for only a relatively short window is helpful when it comes to dating the Torah. If the Torah had been authored by Joseph, for example, we would expect the pharaohs to be named. The same is true if the Torah had been authored on the other side of the “Exodus” and “Judges” periods, perhaps by an Isaiah figure. Yet within this tight mid-to-late second millennium, New Kingdom period, this simply was not done—and that is what we see in the biblical account.

For an author trained in Egypt’s royal court (like Moses), such an omission would be expected and habitual. In fact, if the pharaohs had been named, this could potentially be taken as evidence against the authenticity of the biblical account.

Finally, note the name used to describe God. yhwh (Strongs #3068), the name of the God of Israel, is used over 6,500 times throughout the Hebrew Bible; it is the name used most to refer to God. It is also notably incorporated as a theophoric name element (i.e. Jeremiah, Hezekiah). The use of such names is entirely ubiquitous during the monarchical period and beyond, when late-date advocates suggest that much of the Torah was written.

Yet when it comes to the Torah, we find something peculiar. “There are no names in the Torah based on the name yhwh. … These Yahwistic [yhwh-based] names became so prominent later that the majority of the kings of Judah and about one third of all male Jews had Yahwistic names.” There is one exception to this—Joshua (Yehoshua)—an individual whose name was later changed from Hoshea.

This lack of yhwh-based names in the Torah—despite the fact that this name is used for God throughout the Torah—proves a headache for late-date advocates. Yet the clear reason for this is explained in the Torah itself.

In the account of the burning bush, when God speaks to Moses for the first time, we find the following:

Then Moses said to God, “If I come to the people of Israel and say to them, ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ what shall I say to them?” God said to Moses, “I am who I am” [a Hebrew phrase etymologically related to the name yhwh]. And he said, “Say this to the people of Israel: ‘I am has sent me to you.’” … ‘The Lord [yhwh], the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you.’ This is my name forever … I appeared to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob, as God Almighty, but by my name the Lord I did not make myself known to them (Ex. 3:13-15; 6:3).

The answer for the Torah’s ubiquitous use of this name for God, yet a lack of its use as a common personal name element, then, is simple. The name was revealed to Moses, as author, explaining his regular use of this name to refer to God Himself. Yet it wasn’t known to the general populace to this point for them to start incorporating it into personal names. (The above-cited Haaretz journalist said a lack of evidence of yhwh-worship by slaves in Egypt is evidence against Israelites in Egypt; in reality, this evidence supports the biblical account.)

Thus, it’s not just the names that are used in the Torah that serve as evidence for the date of composition, it’s also the names that are not used. Take Baal, for example. This Canaanite deity was the scourge of Israel in Canaan—from the judges period and all through the period of the monarchy, even beyond. If the Torah were written during this later, first-millennium BC time period, it surely would have contained a warning about, or at least hints of, this specific god. Yet there is no mention of Baal, besides a single Canaanite place-name reference, found in the Torah (Num. 22:41). Why not?

Other common titles, like “Lord of hosts” or “God of hosts,” used nearly 300 times throughout the Bible, are found nowhere in the Torah. “Holy One,” used nearly 50 times throughout the Bible, is also nowhere in the Torah. Why not, if the Torah were written by late Jewish writers under the influence of other biblical texts?

The list of Egyptian-influenced names in the Torah goes on. Several names, “such as Pinhas [Phinehas], show an explicit connection with Egyptian personal names at the period in question, and a few, including Hevron [Hebron] (Ex. 6:18) and Puah (Ex.1:15), are attested as personal names only in the mid-second millennium (that is, the 18th to the 13th centuries BC).”

Think about how well educated in Egyptian history an author writing in the first millennium would have had to be to use such names—and so particular to a specific moment in Egyptian history. “It is one thing to remember a great figure like Moses and perhaps build all sorts of legends around him. It is something else when minor characters and other incidental details that occur but once in the biblical account fit only within the period of Israel’s earliest history and would be unknown to a writer inventing a tradition centuries later.”

We have covered here only a handful of names. There are countless individual words besides, throughout the Torah, which have clear Egyptian derivation. Take, for example, the Exodus 2 account of Moses’s birth: Egyptian-origin words include basket (db3t), bulrushes (km3), pitch (dft), reeds (twfy), river (itrw) and brink (spt).

Knowledge of Egypt

According to Professor Berman (of Bar-Ilan University’s Zalman Shamir Bible Department), “The Torah is infused with Egyptian culture and its response to it. What I find incredibly fascinating is how familiar the Torah is with Egyptian culture, suggesting that the Israelites were indeed in Egypt, and they were there for a long time”.

The author of the Torah was aware that Egyptian women gave birth “upon the stools,” or two bricks or stones (Ex. 1:16). Egyptian women would squat or kneel on these stone bricks during delivery. They are mentioned in papyrus texts, and the first example of such a brick was discovered in 2001—dating to the general, relevant period: the mid-second millennium BC.

The Torah also displays a remarkably good understanding of Egyptian chariotry. Chariots are not mentioned in the Torah prior to the time of Joseph—and indeed, it is just following this time that evidence suggests Egypt began to use the chariot (with the first Egyptian reference of such dating to the 16th century BC). The Torah reveals that by the time of the Exodus, the pharaoh had a huge force of 600 royal chariots used to pursue the Israelites (Exodus 14). Here again, it was specifically during the New Kingdom period that we witness the golden age of Egyptian chariotry. The 13th century BC Battle of Kadesh, for example, represents the largest chariot battle ever fought: the Egyptians fielding some 2,000 chariots against the Hittites. The dating and even the numbers fielded specifically against the fleeing Israelites in the Exodus account, then, are about right.

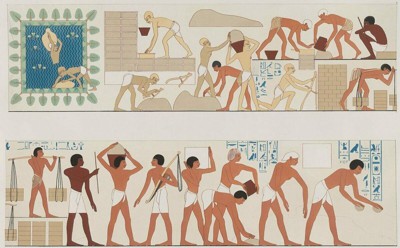

Exodus 5 documents the “recipe” for making bricks out of mud and straw. Were late authors of the Torah also experts in New Kingdom period brickmaking? The same method described in Exodus is famously depicted in artwork on a New Kingdom period tomb, which shows foreign slaves accomplishing the backbreaking labor. Exodus 5 also says that the number of individual bricks produced were “tallied,” or counted. Remarkably, the New Kingdom period “Louvre Leather Roll” (circa 1274 BC) records the tallying of bricks.

Exodus 5 documents the “recipe” for making bricks out of mud and straw. Were late authors of the Torah also experts in New Kingdom period brickmaking? The same method described in Exodus is famously depicted in artwork on a New Kingdom period tomb, which shows foreign slaves accomplishing the backbreaking labor. Exodus 5 also says that the number of individual bricks produced were “tallied,” or counted. Remarkably, the New Kingdom period “Louvre Leather Roll” (circa 1274 BC) records the tallying of bricks.

And what about all of the polities—nations, cities, regions described throughout the Torah that fit with the status quo of the second millennium BC—many of which only belong to this time period?

What about many of the peculiar laws, commandments and statutes found throughout the Torah? Many of these strange laws have led to no end of theories as to their purpose or even relevance. Yet when viewed in light of prevailing Egyptian (and other pagan) culture and customs, especially during the second millennium BC, their raison d’être becomes clear.

There’s the detailed account of the 10 plagues, “against all the gods of Egypt” (Ex. 12:12). Study of these plagues reveals that each was a direct rebuke to various deities in the Egyptian pantheon—again, many of which relate directly to a second-millennium BC setting.

Finally, there’s the simple and obvious fact that many of the later first-millennium BC books of the Hebrew Bible, such as the Prophets—many of which Torah-minimalists say were written before the Torah itself—quote from the Torah. They actually depend on the pre-existence of the Torah in their overall messages.

Conclusion

The internal, linguistic data remarkably and consistently establish that the Torah was written during the second millennium BC. And the text indicates that the author was familiar with the New Kingdom period of Egypt. This means that the Torah was more likely to have been written by Moses, than by someone who lived a thousand years later than this period.

This means that the Torah is factual and not myth or fiction. And the ancient Israelites were slaves in Egypt who escaped to Canaan in the Exodus.

Appendix: The Torah

The Torah (or Pentateuch) is the first five books of the Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy.

References

Christopher Eames, 2017, The antiquity of the Scriptures: The Torah.

Christopher Eames, 2022, Searching for Egypt in Israel.

Randall Price, 2019, Did Moses write the Torah?

Simon Turpin, 2021, Evidence for Mosaic authorship of the Torah.

Acknowledgment

Most of this post comes from an article by archaeologist Christopher Eames of the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology.

Posted, April 2025

Also see: Archaeological evidence of the exodus

Leave a comment